The deposit was located by a visual identification of a set of cracked mortar stones and by using the metal detector. Normally, she would have marked each hot spot picked up by the metal detector with a plastic pin flag, but the fact of the matter was that the entire rise set the detector to screeching its familiar metallic ring, “here, Here, HERE!”

Dr. Scheiber stood on a low slope a few meters west of the Nostrum stage stop, or at least, what remained of the stage stop. Last year they had cleared out the largest bushes and vines but the ensuing year saw the growth of new weeds and grasses in between the stop’s wooden posts and piles of rubble. The sun beat down from a clear sky. It was not so hot as to be unbearable, but it was still early.

Jason, one of her students, was on his knees next to her, using a trowel to carefully remove topsoil from one of the detector’s many hotspots. A harder ting interrupted the softer crunching the trowel made as he scraped through the soil.

“Found something!” he yelled. Dr. Scheiber knelt down beside him as he removed enough soil to reveal the metal detector find to be the tip of a horseshoe. Jason carefully scraped away more soil until the entire horseshoe was exposed. The shoe was the dark color of rust, about 14 centimeters from tang to apex. The tang of a second shoe could be seen resting just underneath the first.

“Go ahead and expose the second shoe as well,” Dr. Scheiber instructed Jason.

***

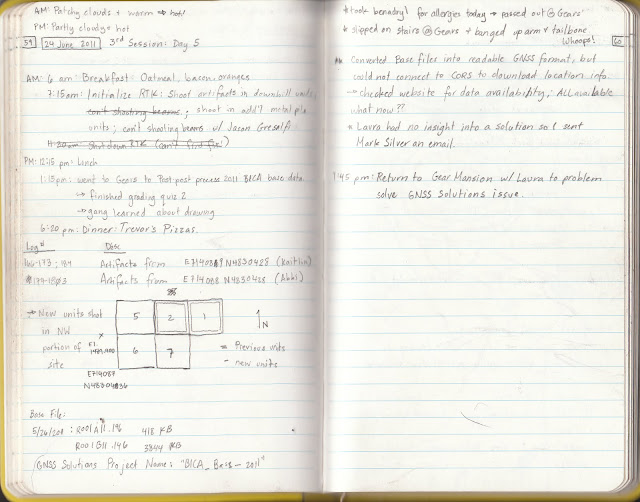

Two days later, a grid of five one-meter by one-meter squares was laid out with nine-inch bridge spikes at the corners and fluorescent-colored nylon grid line along each edge. Six field school students were hunched over the edges of the grid, carefully scraping away soil from a huge deposit of historic artifacts. Jason’s horse shoes were just the tip of a much large trash pile, lying just below the turf of the small rise.

The students spent the following days scraping away dirt, shaking it through mesh screens to look for smaller, overlooked cultural detritus, carefully measuring and drawing artifacts onto large sheets of grid paper, and “coding” each artifact (gathering attribute information about each object and the manner in which it was discovered).

Each day the students revealed more artifacts. On the last day of the field school, a graduate student came with a GPS rover to record the exact placement of each artifact on the top of the pile. Most of the artifacts were still too far buried to be reached. As each artifact’s spatial data were recorded, a student carefully removed the artifact from the unit and placed the object into a plastic bag, labeled with the coordinates of the southwestern corner of the unit the object was taken from and with the depth of the deposit.

The next week saw the return of Dr. Scheiber and her two graduate students. They completed the meticulous task of brushing away and screening dirt, mapping and coding artifacts until each of the five square units was a bare patch of dirt lying several centimeters below the level of the sod and sagebrush.

***

“We’ll need to take a couple of these down some,” declared Katie, one of the graduate students. The Nostrum stage stop was her dissertation project. She had considered the nature of the small rise, and the abrupt end of the historic deposit just below the surface of the ground. In order to better understand the deposition of the hill, she wanted to expose the stratigraphy of the rise. Using square shovels, Katie and the other graduate student spent a morning digging square holes in two of the easternmost units while Dr. Scheiber screened the steady stream of dirt-filled buckets they kept filling.

(PICTURE: Rebecca taking down the unit)

They spent the next morning using their trowels to even out the floor and walls of their hole. The floor of the holes lay about eighty centimeters below the surface of the ground

The last morning on site Katie and Rebecca, the second graduate student, carefully mapped the layers of the northern wall of the hole using a tape measure and a line level. Using Dr. Scheiber’s Munsell book, they identified the type and color of each layer.

Finally, Dr. Scheiber, Katie, Rebecca, Sophie, and Gabriel (Dr. Scheiber’s seven- and five-year-old) methodically shoveled all the dirt they had removed from the ground back into the five units, until the only evidence remaining of the units ever existing was a rectangular-shaped patch of dirt on the ground.

***

(Until next time...)